The most infamous episode in Eastcliff’s first century began with plan to enlarge the dining room and ended with the resignation of a president.

I consulted countless contemporaneous news articles and meeting minutes, as well as interviews with participants. In Eastcliff: History of a Home, I told the full story as succinctly as possible, which turned out to be not very (succinctly).

I felt it important to tell all the facts as they happened, then present an analysis of what went wrong. For the post-mortem summary, I relied heavily on many recorded interviews with participants who were there at the time and, sometimes with a few years hindsight, shared candidly both what occurred and their opinions of causes. The distillation of that research couldn’t fit into the book, so more of that text is included here.

This article, like all the Eastcliff supplemental information on this website, is intended to be read as an addition to the book, and it may be a bit confusing when read alone. Nonetheless, I will give you a very brief summary of what happened, as that is covered extensively in the book, and an expanded version of why it happened, as that is summarized briefly in the book.

1968 Eastcliff remodel (never built)

In 1968, the regents sought to expand the dining room and entertaining space at Eastcliff, and obtained a $70,000 bank loan. President Malcolm Moos felt the time wasn’t right politically to make such changes.

During the Magrath administration, the regents again pursued the remodel, with deferred maintenance increasing the need. Again, due to budget pressures and public relation concerns, the president suggested they wait until the presidential transition.

When Ken Keller was elected president in March, 1985, plans were already underway for renovation; he asked for the construction to be finished before he moved in.

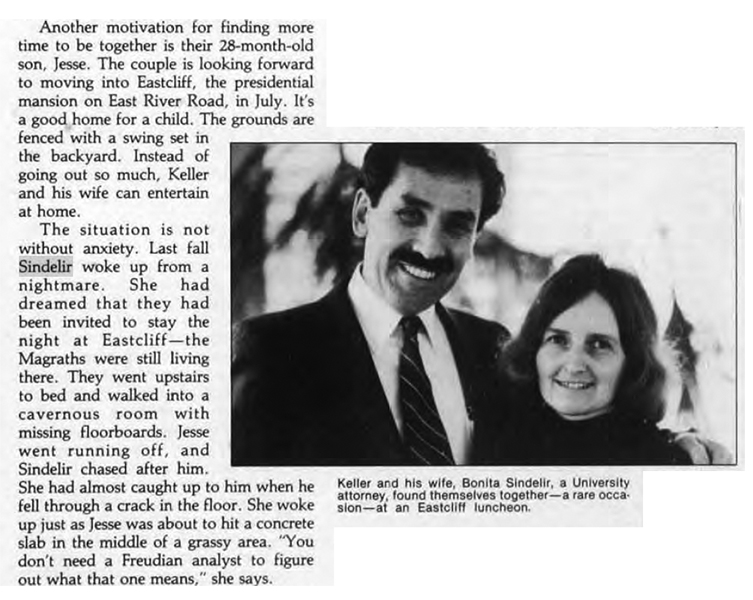

A special edition on Minnesota magazine announced the new president, and included a prescient nightmare that Bonita Sindelir had about Eastcliff.

After months of waiting without the construction beginning, the Keller family moved in.

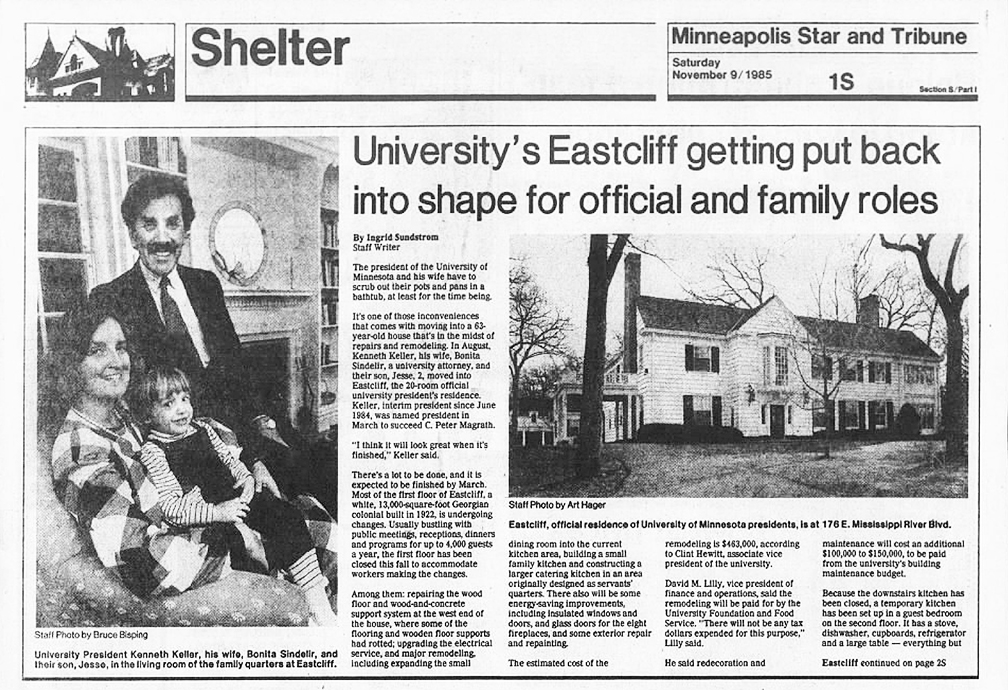

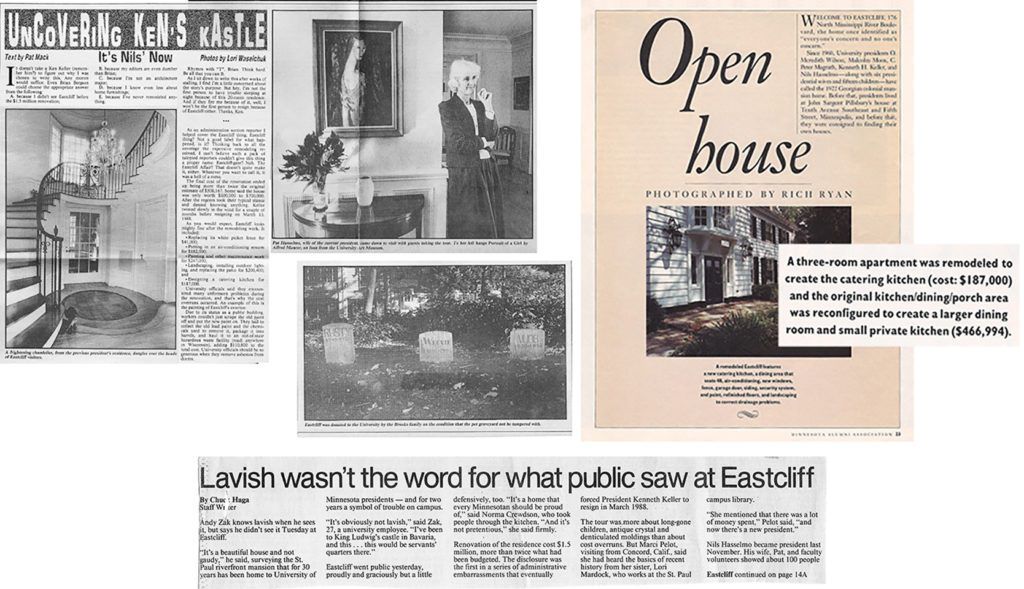

When the project began in November, 1985, the regents toured the house, along with reporters, and the scope of the project appeared in the newspaper. The project grew to include a terrace replacement and repairs needed due to years of deferred maintenance. The regents visited Eastcliff regularly for dinner and tours.

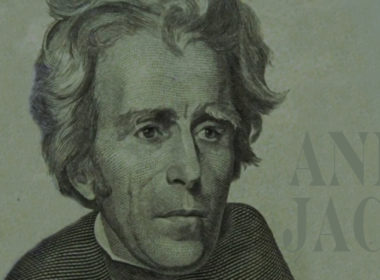

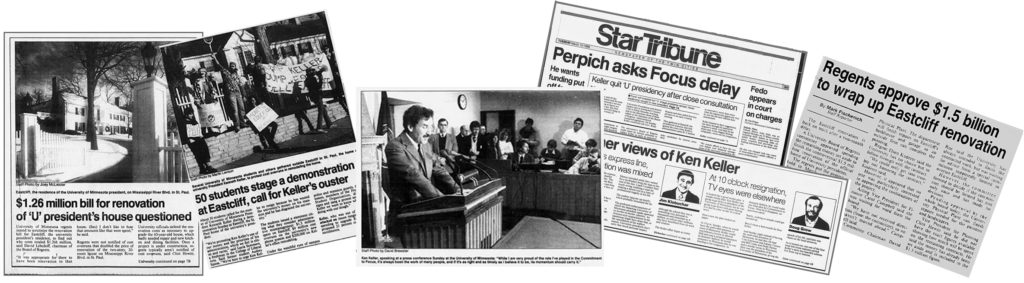

Just over two years later, in January 1988, the Minnesota Daily reported cost overruns. A month later, the city newspapers picked up the story, then ran (mostly) negative stories daily for six weeks. A few of the regents (who were opposed to the progressive president on other matters) claimed they had never heard anything about the project. President Keller resigned on March 14, 1988.

A 1985 newspaper article reported the planned renovations.

Later some of the regents said they knew nothing about the plans.

Minneapolis Star and Tribune, November 9, 1985

Minnesota Daily, January 7, 1988

In month of March, 1988, there were sixty-eight stories that mentioned Eastcliff in the Star Tribune alone (twenty-nine in the nearly two weeks leading to the resignation, thirteen that were about the resignation, followed by twenty-six stories in the last two weeks of March). Like a dog refusing to give up a bone, there were sixty-two stories mentioning Eastcliff from April through December.

How Did Things Go So Wrong?

University historian Ann Pflaum said, seven years after Keller’s resignation, “I think if any one of several factors hadn’t been present, he probably would still be president. That’s how close I think it came to being a sort of act of the gods and a kind of a fatal encounter.”

(Ann Pflaum was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on August 16, 1995. Ann was described as former member of the Department of History and associate dean for Continuing Education and Extension. She later became University historian.)

Many people, often with years of hindsight, have expressed opinions as to what those myriad factors were, and some have done so on the record. I will share some of those opinions with you.

Opposition to a Commitment to Focus

Student body president Judy Grew was quoted the night of the resignation as saying that the criticisms were a “smokescreen” for opposition to the Focus plan.

“A lot of people who have called for his resignation have opposed Commitment to Focus. I think internally the plan will survive, but it won’t have the same flavor. . . Now if [legislators] don’t like Commitment to Focus, they’re going to have to say what their alternatives will be.”

(Paul Dienhart, “Six Weeks That Toppled a President,” University of Minnesota UPDATE, April 1988.

A Commitment to Focus was succinctly summarized in Stanford Lehmberg and Ann Pflaum’s The University of Minnesota 1945–2000 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001):

“Among the principal elements in Commitment to Focus were strengthening graduate education and research, reducing undergraduate enrollments to improve the undergraduate experience, strengthening preparation requirements, and transforming the General College from a degree-granting program to one that would offer developmental and enrichment skills. Each of the colleges was to focus on areas of unique strength, particularly research. Undergraduate enrollment reductions would occur naturally as a result of demographics and also through encouraging more students to attend community colleges before transferring to the university. Implicit in the plan was that through focus, the university could move up from the top ten into the top five among public research universities. In return, the state was asked to continue to fund the university at current levels despite pending enrollment declines.”

John Wallace, assistant vice-president for academic affairs during the Keller administration, said,

“I think the real resistance to Ken was over Commitment to Focus and then to grand policy directions that offended a lot of constituents of the university. . . It made me realize what a complex coalition the university is. It’s really about as big as the state of Minnesota, 300 miles wide, and 200 miles deep, and in a lot of ways about an inch thick in terms of the really solidarity behind the coalition. . . . I think a lot of constituencies began peeling off. . . . Anyway, the regents abandoned him.”

(John Wallace was interviewed by Professor Clarke A. Chambers on September 8, 1994. Wallace was a professor and chairman for the department of philosophy; former staff member for the graduate school and vice-president for academic affairs.)

Wally Hilke, who was a regent at the time, explained,

“Ken was burdened, rightly or wrongly, by having a very difficult board to deal with. I believe five of the regents consistently voted against whatever Ken wanted, or needed a great deal of cajoling, or needed resolutions designed specifically for them.”

Hilke said that the regents were split evenly between regents with the philosophy that the University should try to accept all Minnesota applicants, and regents who agreed with the Commitment to Focus philosophy of prioritizing and “doing a very good or excellent job of whatever we tackle.”

Hilke continued,

“Several regents felt that the Land-Grant mission of the university truly mandated that we make ourselves accessible to all comers and even if we can’t make a spot available for every student in the state who wants to attend the university, we certainly should not move in the opposite direction. Those regents who were philosophically in that camp would include, I think: Mary Schertler, Wenda Moore, Stan Sahlstrom, Wendy Anderson, and Dave Roe. On the other side, we had a number of regents who bought into the philosophy of Commitment to Focus thinking that the university has to marshal its resources wisely, prioritize its programs, and that we serve the state best by doing a very good or excellent job of whatever we tackle. The regents that stood on that side were: Lebedoff who was the leader of that group, both the rhetorical leader and political leader, I think, Peg Craig, Chuck Casey, Elton Kuderer, Wally Hilke, Irv Goldfine … I’m missing one regent.”

[Hilke lists a five to five split, so two of the twelve regents are missing from his list: Jack Grahek and Charles McGuiggan.](Wally Hilke was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on September 21, 1994. Hilke, lawyer for the law offices of Lindquist and Vennum, had been associated with the department of political science, the student senate, and the Board of Regents at the University.)

Populism

D. J. Leary, a public affairs consultant who was working with the University at the time, said,

“I have to talk for a moment about the birthright provision, or the sense of birthright. I’ve talked about it to other people. There was prior to 1980-ish a sense in Minnesota that it was the birthright of the sons and daughters of farmers, and miners, and engineers, and working people that when they were born, they could go to this university. More and more, and increasingly, fewer were even applying. They were going to the state universities and what have you and then we saw the explosion of St. Cloud, and Mankato, and that. They had this ongoing affection and identity and many could easily blur the lines that St. Cloud State University was part of the University of Minnesota. I heard that many times. Then, comes Commitment to Focus and for the first time ever somebody says publicly, ‘That’s not true. We’re only going to take certain kids and we’re going to improve that.’ I want to tell you as one who went throughout the state and took the temperature and the pulse it was the major blow to the university, the university’s long sense of ground and grassroots feeling, out there. I mean, it was palpable.”

(D. J. Leary was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 3, 1995.)

Ken Keller responded to the concerns about admissions standards,

“We are not denying access so much as providing clear choices. By setting standards, we will establish what it is that we have to offer at the University, what it is we think constitute a very high-quality education. Any student who want that challenge will be welcome.

(Kenneth Keller was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 23, 1997.)

Shortly after Keller’s election as president, before the renovation work began on Eastcliff, he was interviewed by Minnesota magazine. He gave the cited quote in answer to, “How do you respond to charges of elitism?” His answer, referenced in the text, continued,

“Far from being an elitist plan, it is a plan to offer choice to people and to offer the opportunity for a high-quality education. I think it was a governor of California in the recent past who said that public institutions should serve for education of the masses—if you really wanted high-quality education you went to a private school. That’s elitism. My vision of the University as a public institution offering that choice of high quality is the opposite of elitism, it’s opportunity. It’s opportunity for people regardless of their economic backgrounds to have the possibility of very high-quality education in the public sector.”

(Maureen Smith, “Access to Quality”, Minnesota, Special issue 1985.)

The Keller administration sent letters to the parents of every eighth grader in the state. Keller said,

“In four years, these are going to be the university requirements. You ought to be making sure that your high school counselors are advising your kids to take these courses. That was a very important principle which was how, in a populist state, can you improve the quality of the university without being subject to the cries of elitism? Of course, you can’t avoid it.”

(Kenneth H. Keller was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on December 1, 3, and 8, 1997.)

Communication

The public, it was said, did not understand Commitment to Focus. George Robb, associate vice president for institutional relations during the Keller administration, said,

“You can go to the documents and it’s self-evident in the documents that a lot of what he was talking about were changes that needed to be made at the undergraduate level. He cared deeply about improving undergraduate education. Yet, the news media sound byte that developed for describing Commitment to Focus was “Ken Keller’s plan to emphasize research and graduate education.”

(George Robb was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on August 22, 1995.)

Ken Keller gave talks around the state about the Commitment to Focus plan. He estimated that during his three years presidency he gave two hundred talks per year to an average of a hundred people, reaching sixty thousand people directly over three years. However, he realized, most of the state’s four million residents got their impressions from some other source.

(Kenneth H. Keller was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on December 1, 3, and 8, 1997.)

Meanwhile, according to D. J. Leary, Roland Dennistoun, deputy commissioner of agriculture, “would take gratuitous speaking engagements around the state just to attack Commitment to Focus on some very narrow thing. He said,

“They’re going to close down education, and they’re going to close down agriculture, and try to run everything in a secondary position.”

(D. J. Leary was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 3, 1995.)

Why doesn’t the University tell its story? In my experience during my husband’s presidency, Eric would speak to some facts like a broken record. (To any young readers: old vinyl records would get a scratch, so the needle would go back in the same grove and keep repeat the same thing over and over and over and over.) I would repeatedly hear those same facts in speeches, then on Minnesota Public Radio (MPR), and also see them in University press briefings. Invariably, someone would hear one of those facts and exclaim, “I didn’t know that! The University should do a better job of telling their story.”

The University’s (2011–2021) four-billion-dollar campaign, Driven, was about telling the University’s story and inviting investment, and exceeded its goal. The Keller-era Minnesota Campaign raised $364 million—well over its $300 million goal. Even in the midst of the Eastcliff negative publicity, donors who were really paying attention heard the true story and showed their support for the University, and apparently for Commitment to Focus.

Russell Bennett served as Chair of the Minnesota Campaign. Bennett said,

“It was amazing. We ended up setting the goal at $350 million and we ended up with $365 million. You can always say if but if the Eastcliff situation hadn’t come along, we’d have hit $400 million because we hadn’t even started the public campaign.”

(Russell Bennett was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 4, 1995. )

The news media, as you will soon read, was not helpful. D. J. Leary said,

“I used to say to these editors over lunch, ‘You know, it is time for somebody to say that a university is a repository of our humanity. . . This is a gift and that you send a message if you say, ‘This is a gift of the university and we’re going to sell it or get rid of it.’ I said, ‘You can forget about getting any of the great manuscripts and that if you’re going to have a role as a repository of research and what have you.’’ But nobody was making those cases on behalf of the university because it was just too hot to touch.”

Many faculty members understood and supported the president’s plans. A group of fifteen top faculty wrote to Regent Lebedoff saying they were “gravely concerned by the exaggerated treatment that the renovation of Eastcliff has received in the media” and saying that the U is “very fortunate in having Keller at the helm at this time and that he has the potential to become the outstanding president of the last half century.”

(Brief (an internal University bulletin), March 2, 1988.)

The desk

At some point during the Keller presidency, a University designer remodeled the president’s office and President Keller gave approvals. During the Eastcliff news frenzy, it came to light that the Morrill Hall office remodel cost $200,000, including a $9,535 desk and $6,286 credenza ($15,822 total). The total ($200,000) figure included air conditioning a wing of the building, and heat for the outer office. The Foundation covered the cost of furniture with donated funds. The reasoning was that, in the past, if the money did not come from State funds there was little scrutiny. The Eastcliff renovation was, likewise, not funded by the State and therefore not expected to be an issue. When the cost of the office furniture became public, Keller offered to reimburse the University for the desk and credenza.

According to Ken Keller,

“At one time, in fact, some reporters arrived and decided that when I had that desk put in, I had absconded with Peter Magrath’s desk and put it in my summer home. That was the rumor. When they came in, I said, ‘I haven’t done that.’ They said, ‘Where is it?’ I said, ‘I don’t know where it is.’ Actually, we spent—several people were turned to—four or five hours looking through Morrill Hall and, finally, found it. They came down and they took a picture of it.”

(Kenneth Keller was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on December 1, 3, and 8, 1997.)

Elmer Anderson said,

“I remember with some amusement how nobody wanted to touch that [the Eastcliff renovation]. Ken Keller had the courage to do it and a lot of the things related to union relationships between the university, and the legislature, and organized labor; so, there would be labor groups standing by while other groups were doing work. It was costly but the only real mistake Ken Keller made was to order too fancy a desk for himself. That caught the public attention and that did him in.

(Elmer L. Anderson was interviewed at his home by Professor Clarke A. Chambers on October 2, 1995. Elmer L. Anderson (1909–2004) was governor of Minnesota (1961–1963), University regent (1967–1975), and trustee of the University of Minnesota Foundation (1968–1988).)

Change orders, in addition to unexpected costs

The asbestos, rotten wood, and lead paint are detailed in the book. Russell Bennett said,

“Poor Bonita [Sindelir, wife of Keller], it wasn’t her idea to redo Eastcliff. The place was falling apart. It badly needed doing. Like a lot of things, Ken was working hard on the campaign, and running the university at the same time, and I can just see the scene. He’d come home at night and say, ‘Well, how did things go today?’ Poor Bonita would say, ‘I don’t know. The contractors had to start over again because . . .’ this or that. You can just imagine the overruns. But in hindsight, you know, it really was, compared to the $365 million raised, a nothing issue but the press had fun with it.”

(Russell Bennett was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 4, 1995.)

There were also changes and additions to the project. The legislative auditor’s report (released March 10) stated that the September 1985 estimate for the project was for $1.1 million. Items were cut to reduce costs, and then added later. For example, when the air conditioning was added later, rather than adding $112,000 to the cost, it added an additional $191,000 because it was done piecemeal. The most cringeworthy part of the auditor’s report, in my opinion, was the heartless suggestion that the University missed the opportunity to tear down Eastcliff and build a new house for less money.

A Hawaiian vacation

In late February, Ken and Bonita took their son on a long-planned, week-long vacation. They had made the down-payment on the trip a year earlier. Ken said that they had not had a proper vacation the year before, and his son would “never be five again.” Nonetheless, the newspapers comments about the President “doing the hula” in Hawaii.

(Paul Dienhart, “Six Weeks That Toppled a President,” University of Minnesota UPDATE, April 1988.), while the general public endured a Minnesota winter, didn’t help with public relations.

The media war

The only levity is supplied by a typo in the headline that changed the $1.5 million budget to 1.5 billion with a B

Wally Hilke explained the battle in the media,

“Both of the big city newspapers were terribly embarrassed that they had been scooped by the Daily on the most sensational story at the university in years. Then, they were assigning two reporters at a time, three reporters at a time, to do an investigative work on the university asking for copies of financial records that had never been scrutinized by the media—and that continues. A lot of the reporting truly is unfair. That’s changed the university’s relationship with the media. It’s not just that we’re getting negative press, it’s that we’re not getting the positive press that the university needs to maintain its reputation in the state and to enhance its reputation.”

(Wally Hilke was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on September 21, 1994.)

“Both of the big city newspapers were terribly embarrassed that they had been scooped… Then, they were assigning two reporters at a time, three reporters at a time, to do an investigative work on the university asking for copies of financial records that had never been scrutinized by the media—and that continues. A lot of the reporting truly is unfair. That’s changed the university’s relationship with the media. It’s not just that we’re getting negative press, it’s that we’re not getting the positive press that the university needs to maintain its reputation in the state and to enhance its reputation.”

Wally Hilke

Minnesota alumni magazine shared more details:

“The situation escalated when columnists Nick Coleman of the Pioneer Press and Doug Grow of the Star Tribune, whose papers had recently engaged in a circulation war that demanded big headlines and dramatic stories, started to criticize Keller for being arrogant and extravagant.”

(John Kostouros, “The Keller Chronicles,” Minnesota, March/April 1993.)

There were some more balanced stories, such as one the week before the resignation by architectural critic Linda Mack . As she described it:

“[Eastcliff had] been renovated at a cost that has egalitarian Minnesotans screaming. But before we conclude that the $1.5 million remodeling is the worst scandal to hit the state, let’s take a tour of the place.” She described the need for the work, and described the work as well-executed, concluding “Eastcliff’s renovation was a first-class job, inside and out. Undoubtedly, doing less at less expense would have been wise. But doing nothing and letting the property deteriorate, or cutting corners and making it tacky, would hardly have been wise. Having a public house is no excuse to spend too much, but neither is it a justification for spending too little.

“Architectural scandals abound. Ugly buildings blight our environment; historic buildings are destroyed; cities spend millions of dollars of taxpayers’ money to support projects that feed developers bankrolls and sap the city of life. Eastcliff’s renovation just doesn’t qualify as that kind of scandal.”

(“Eastcliff’s renovation a Good Job,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, March 8, 1988)

While newspaper front pages blared with critical headlines, columnists wrote opinion articles meant to entertain more than enlighten. Calls for perspective appeared mainly on lesser-read editorial pages. The mistakes made were “small potatoes compared to the damage Minnesota would suffer if Commitment to Focus progress stopped,” stated a Star Tribune editorial. A St. Paul editorial likewise warned that the University and the people of the state would be the losers if Keller was forced out of office.

State politics and lack of legislative support

Ken Keller and David Lilly had an important success working with the Legislature. I will use David Lilly’s words to describe it:

“Now, the Permanent University Fund goes all the way back to the Land-Grant days. These were funds that were generated from the sale of lands that came to the university. The legislature said, “Any monies that you earn on those funds, we will offset in our budget.” . . . I went to the legislature and said, “Look, let us use the Permanent University Fund as a matching fund and we will generate dollar for dollar, every dollar that we put into these chairs [endowed chairs for professors], we’ll get the private sector to match it, and don’t you offset that.” It didn’t cost them much because the amount of money they’re talking about was five percent of whatever we raised. All we were asking them to do was turn over the Permanent University Fund for matching purposes.

“These matches helped significantly to create over a hundred new endowed professorships at the University.”

(David Lilly was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 11, 1994.)

Other legislative endeavors did not go as well. Ken Keller had been a legislative lobbyist for the Twin Cities faculty, and, as such, had lobbied for stronger support for graduate programs on the Twin Cities campus rather than on the University of Minnesota Duluth campus.

Wally Hilke said,

“Some will tell you it was the residual effect of Ken’s battling legislators from the Eighth Congressional District for years, and years, and years, giving them the opportunity with Eastcliff, and the office furniture, and some other matters . . . he was constantly battling the folks from the Eighth Congressional District who were always nipping at him but once they had some more serious material to work with, they were able to do a lot of damage to the administration over at the legislature.”

(Wally Hilke was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on September 21, 1994.)

Wendell Anderson, a former governor as well as former regent, said,

“How President Keller got in trouble is that he somehow conveyed the impression that the university was not a good place as opposed to saying, in my judgment, that it was a great place that should be better. Soon, I think, the public and key legislators became disillusioned. . . . it really offended legislators who’d been putting all kinds of money into it, had graduated from it. . .

(Wendell R. Anderson was interviewed by Ann M. Pflaum on June 1, 1999. Wendell Anderson was a student at the University from 1950 to 1954, was member of the silver-medal winning US Olympic hockey team in 1956, and graduated from the University Law School in 1960. He served in the Minnesota Legislature (1959–1971), was a governor of Minnesota (1971–1976), US Senator (1976–1978), and member of the Board of Regents (1985–1997).)

The regents were (and are) all elected by the Minnesota legislature, and regents may feel beholding to them. On March 10, 1988, the Star Tribune reported,

“Meanwhile, regents have not been perceived as doing much to help the situation.” Rep. Glen Anderson, DFL-Bellingham, chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, said regents also ‘have a lot of egg on their face right now. If they don’t do something quickly, it’s going to be smeared all over their faces.’

“Regents visited Eastcliff, some more than others, while the $1.5 million project was in progress, and none of them raised questions. The sum of improvements—central air conditioning, an expanded dining room, a catering kitchen, a patio, a block-long fence—didn’t set off many alarms until reporters started investigating.

“Having regents elected by the Legislature should guarantee a board with enough political savvy to keep the university from stumbling into embarrassing situations.”

(“‘U’ must solve communication and credibility problems,” Star Tribune, March 10, 1988.)

Lack of support from the regents

As described in Eastcliff: History of a Home, the regents were being entertained at Eastcliff throughout the renovation. They were there at least two to three times a year, and as Ken Keller said,

“They wanted to see every detail of every change. Every time they were there over the past three years, we’d gone through and we’d shown them, this much has been done and this much hasn’t been done. Of course, in the public setting, they were put on the spot.”

(Kenneth H. Keller was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on December 1, 3, and 8, 1997.)

David Lilly said,

“Eastcliff was a university property that had been given to the university and it was falling apart. . . . So, we went to the regents and said, ‘How should we do this?’ I’ll never forget Wendell Anderson saying to me, ‘Don’t bring this to the regents. You know how to do it. Pay for it a little out of this account and a little out of that account.’ The regents all knew that we were going ahead and renovating. All the regents knew, informally, that we were going ahead and they had all agreed. But unfortunately, it was one of the major errors in my administration. We should have taken the project to the regents and gotten their approval in writing. We did not. We thought the verbal, informal, approval was enough.”

(David Lilly was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 11, 1994.)

Richard Sauer, who was a vice president under Keller and then interim president after him, said that Regent McGuiggan, who was board chair during the renovation, gave verbal approval for Eastcliff cost overruns and then said there was no approval.

“The regents insisted he live there as part of the appointment agreement and then he said, ‘You’ve got to do something with the place.’ The regents had set aside some amount of money, $600,000, as an amount of money that could be spent on it. He started having Physical Plant people and others look at it and they realized what a desperate state it was in. The place was falling apart. Ceilings had to be taken out, and timbers replaced, and you name it. Pretty soon the estimate was $7-, $8-, $900,000 and more. He went to the chairman of the board at the time, Chuck McGuiggan, and said, ‘It’s going to go far beyond this,’ and Chuck said, ‘That’s okay, just do what needs to be done.’ Then, later, those same regents used it as a … you went far beyond … you didn’t have authority … [He had] spoken authority and then the same reasons were used to undermine him when they couldn’t stand the heat around Commitment to Focus.”

(Richard Sauer was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on July 17, 1995.)

Wally Hilke said, “The fundamental problem Ken had is he didn’t have strong support on the Board of Regents; and so, he wasn’t able to move forward with his programs.”

After the weeks of negative publicity, D. J. Leary said of the regents, “They’re hanging them out to dry. I mean, Dave Roe goes on Almanac on that Friday night, and I look at what he says, and I said, ‘This is it.’”

Leary continued with his opinion as the why the regents didn’t support the administration, “The whole thing about governance and the Board of Regents, the problem, and it continues all the time, is these are political people. It’s a political job.

“…people started labeling him, ‘an Easterner,’ ‘a New Yorker’ and while they never said ‘Jewish,’ there was this, you know, he isn’t the religious bent of most of the folks here in Minnesota.”

“That’s the way they’re appointed, and that’s the way they react, and that’s [how] they act about everything whether it’s tuition increases or what have you. It’s really measuring the impact that’s going to happen on them, and the people who support them, and their chance to get re-elected the next time. I will tell you, I plan in my twilight years to put them in my book, “Profiles in Jello” because there’s no real courage. They want to act in more of a herd instinct and they don’t go out to touch the people to really communicate about this university.”

(D. J. Leary was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 3, 1995. Don’t you wish Leary would tell us what he really thinks? No word yet on a publication date for “Profiles in Jello.”)

“The whole thing about governance

D. J. Leary

and the Board of Regents, the problem,

and it continues all the time, is these are political people. It’s a political job. That’s the way they’re appointed, and that’s the way they react. . . . I will tell you, I plan in my twilight years to put them in my book, Profiles in Jello. . . ”

Antisemitism, or just a difference in style?

Richard Sauer said,

“Ken had been here over twenty years at the university. It was his life. He truly believed in it and was committed to it but as soon as he started proposing change that was not comfortable to some folks, people started labeling him, ‘an Easterner,’ ‘a New Yorker’ and while they never said ‘Jewish,’ there was this, you know, he isn’t the religious bent of most of the folks here in Minnesota.”

(Richard Sauer was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on July 17, 1995.)

Minnesota magazine pointed out that while President Keller was from New York so was President Magrath, and no one seemed to mention that, and “More than one person has suggested anti-Semitism played a role in the demise of Keller, who is Jewish.

(John Kostouros, “The Keller Chronicles,” Minnesota, March/April 1993.)

“Something I suppose I shouldn’t be saying is, I felt there was more anti-Semitism in Minnesota than anyplace I’ve been.”

Neal A. Vanselow, M.D.

Neal A. Vanselow, vice president of Academic Health Center(1982 to 1989), said,

“Ken Keller was one of the brightest I’ve worked for. . . I thought he was a good president and terribly treated by the regents, and by the state, and by the University. Something I suppose I shouldn’t be saying is, I felt there was more anti-Semitism in Minnesota than anyplace I’ve been.”

“During the time Keller was under attack by the regents, the newspaper, and everybody else, [a Star Tribune columnist] wrote a column in which he said that—I’m paraphrasing [unclear]—this man will never understand Minnesota because he’s not one of us, or something to that effect and chided him about his mustache, that he looked like Groucho Marx. You could almost read Jew in there. It shocked us. We hadn’t experienced that anyplace. Chuck McGuiggan, a regent, later I think was also chastised for anti-Semitic remarks. We saw more of that than at any other place, and I think that affected Ken’s presidency, to some extent.”

(Neal A. Vanselow, M.D., was interviewed by Dominique A. Tobbell for the Academic Health Center, July 10, 2013.)

In the book Professor Berman (Hy Berman with Jay Weiner, Minnesota Press, 2019), historian Hy Berman explains that Minneapolis was anti-Semitic while St. Paul was much less so, and that antisemitism was used by political opponents of Governor Floyd B. Olson, who, while not Jewish, grew up speaking Yiddish in North Minneapolis.

Perhaps it was just a matter of style. Dianna Gardner worked in the president’s office for 30 years, beginning as principal secretary in 1970. She described the presidents in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s.

“I think Ken Keller is a very, very bright man. He got a bum rap in some ways. I think his heart was with the university; he’d been here for twenty years. To be characterized as somebody coming from New York with a New York attitude—I’ve heard that said about him—he’d been here for a long time and he loved this university and still does. Maybe some of his ideas were ahead of what people wanted to do. Maybe he was looking for change too fast. There again, I think it was his working style; how he worked was not how Peter Magrath worked. You add ten years of working under one type of arrangement with Dr. Magrath, who consulted widely on everything, to Ken Keller, who made decisions and stuck by them. I think President Hasselmo, over and over again, has said that he was continuing the work that President Keller started. Hasselmo’s was a different approach to communicating it and to following through with it, but it was based on President Keller’s thoughts and ideas.”

(Dianna Gardner was interviewed by Ann Pflaum on February 21, 2000.)

But then again, Regent Charles McGuiggan was board chair from 1985 to 1987. In the summer of 1988, after Keller’s resignation, Regent McGuiggan was accused in articles in Twin Cities magazine (August 1988) and the Star Tribune (July 22, 1988) of making anti-Semitic comments.

Racism, or just protection of union jobs?

The University physical plant was doing the work at Eastcliff. According to Ann Pflaum, David Lilly said to her friend and mentor, Bill Thomas, “You’ve done such a good job in Personnel, why don’t you take on the Physical Plant as well?” He made him [in charge of the] Physical Plant. You had much more deeply seated racism in the Physical Plant.”

Ann explained that the number two hired was, like Bill, a black man, “so, that was one of the subterranean issues in the ouster of Keller was the deep resentment of the blue collar trades groups in the Physical Plant who had two black men saying there were going to be major changes in this organization and that was more than that culture could stand.”

“[There] was deep resentment… in the Physical Plant who had two black men saying there were going to be major changes in this organization and that was more than that culture could stand.”

Ann Pflaum

Ann did not suggest that the workers purposely caused the cost overruns (although the paint scraping, in my opinion, was problematic), but rather they were the source of the negative publicity. Ann continued,

“They began leaking fence stories and then began leaking stories about cost overruns, in part, to get back at Bill Thomas and to get back at David Lilly for appointing Bill Thomas. . .

“He [David Roe] was a regent in the Magrath/Keller crisis years. I think he and McGuiggan, a dentist from southern Minnesota, allowed themselves to become captured by a union point of view and allowed themselves to carry the anxiety, to help publicize. They were in part the conduit through which these leaks occurred.”

Ann concluded,

“The Magraths started the repairs, the idea of repairing even before Magrath took the other job, there was a small working group—I happened to be part of that—to repair Eastcliff. So, you have a jumble of ironic circumstances contributing to a kind of blowup that got out of hand. Let me summarize what I think they are. One of them is the hostility of race where the Physical Plant was eager to leak to get back at David Lilly for the African-Americans in their midst—nothing to do with anything else but they’re angry. Another issue is Ken’s propensity to be able to fix almost anything, the irony, the accident of the absence of David Lilly [who was in the hospital] . . . so the fixer was Ken himself, which focused all the attention on him. Another ironic coincidence was there was a newspaper war that fall and the newspapers were vying each other for sensational stories. Between St. Paul and Minneapolis, so that everybody was out for anything that was newsworthy. So, that was another factor in the situation.”

(Ann Pflaum was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on August 16, 1995.)

This was not the only source suggesting the Daily got their information from Regent McGuiggan. (Ann made these remarks in a 1995 interview. I asked her in December 2019 if she maintained the same view of the situation, and she confirmed she did, sharing the same story.)

Now it is possible that the leaks and complaints had more to do with labor issues than racism. Ken Keller explained that

“[Bill Thomas was] trying to reorganize the Physical Plant administration which was a very horizontal administration in which there were many, many workers, employees, union people and very few management people and great inefficiencies, almost featherbedding-like inefficiencies. If you sent somebody out to put up a painting in your office, two people went out: one to drive and the other to hang the painting in the office. The driver stayed and waited downstairs while the worker did the work.”

“You’ve got a real problem. You’ve got to fire this guy Thomas. He’s causing lots of trouble in the Physical Plant.”

Regent David Roe to Ken Keller

Bill Thomas was looking into a restructure with one manger over forty workers. Ken continued,

“Dave Roe was a regent, the head of the AFL-CIO and he said, “You’re moving money from workers to management and that’s the wrong way to go. We think this guy, Thomas, is all wrong.” Worse than Roe—Roe in his opposition was always very open—was that some people in the Physical Plant structure got to Chuck McGuiggan, the chairman of the board. . . . Chuck came to see me during that time. He said, ‘You’ve got a real problem. You’ve got to fire this guy Thomas. He’s causing lots of trouble in the Physical Plant.’

“I said, ‘Chuck, I can’t do that. He’s got the authority. I don’t have any reason for second guessing him. He’s been open in these recommendations. He thinks they make sense. Dave Lilly thinks they make sense. I don’t think I ought to sit here and make a different judgment because they make sense to me, too.’ He said, ‘It’s going to cause a lot of trouble.’ This was, perhaps, November of 1987 or thereabouts. Now, I have some things I’ve pieced together after the fact. January of 1988 is when, all of a sudden, an article appears in the Minnesota Daily . . . a great revelation about the money being spent at Eastcliff. The thrust of it was that this was information they got from secret sources in a revelatory way; that is, it was revealed to them otherwise secret. They didn’t bother to find out that none of this was secret; that is, it was all known because we’d been through it.

“In subsequent conversations—Clarke, we all have to put this in some perspective—my friends on the Daily, reporters, said, ‘You know where we got this from? We got it in anonymous telephone call from someone that everyone of us knows was Chuck McGuiggan.’”

(Kenneth H. Keller was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on December 1, 3, and 8, 1997.)

D. J. Leary was more candid about David Roe being the president of the Minnesota AFL-CIO (1966 to 1984) overlapping the time he was a University regent (1981–1993), and following another labor leader, Neal Sherburne:

“Well, there’s some awfully good labor deals around the university here. The university’s relationship with labor has been very good for labor. It’s only come into question somewhat in recent years. . .

“Talk to people who have to put in a window air-conditioner. You can go to Best Buy and put one in and it would be $200 or $300 but you go through Plant here at the university, it ends up being on your budget at about $1,800 to get somebody to come over and put this thing in. So, while there was some of the rumbling, it was well acknowledged that the university was a good friend of labor.

(D. J. Leary was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 3, 1995.)

The central reserves, a.k.a. the “slush fund”

George Robb, associate vice president for institutional relations during the Keller administration, spoke about the central reserves:

“If there was a scandal about reserves, it was that managers out there all over the university had these little cubbyholes of reserve funds. . . What Dave Lilly did, to his credit as far as I’m concerned, is he really found out where all that stuff was. He went out and pretty actively said, “Folks, you’ve got twice as much money as you’re going to need. . .”

Then Robb said Lilly told them, “Folks, we’re going to scrape up a bunch of that loose change, and make it a university reserve, and spend it on university priorities.” Lilly invested the money well, and it grew.

Regarding the regents, Robb said,

“[Keller’s] primary supporters on the board, in my view, were not willing to step up to the plate when it really got threatening. I think some of his strongest ones got quiet in a hurry. Some of those that he had alienated by not paying a lot of attention to just gained strength through all that. . . That’s part of history that probably will have to wait because there won’t be very many people who feel free to talk really openly about some of this stuff. I happen to think that there were board members who had a lot more knowledge of what was going on . . . for example, with the Eastcliff expenses. When that became a big public issue, they ran for the hills.”

(George Robb was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on August 22, 1995.)

Edward Foster, associate dean of academic affairs beginning in 1986, said the regents were told about the central reserve:

“They were aware of it in that they were told about it. They were aware of it in that the income from central reserves was a matter of regular financial reporting to them. It was part of the meeting that they all dozed through while somebody goes over the numbers. They were not interested in it, and nobody was alert to either the political volatility or the amount of money that was being generated and was at central administration’s discretion.”

An amusing observation that Ed Foster made was that William Middlebrook, comptroller and vice president from 1925 to 1959, supposedly

“kept accounts very close to his vest, and that he would have both the president and the academic vice-president coming to him essentially in supplication when they wanted to do something, and would come in and ask him if money could be found to do it. He would pull out this little sheet and at least on some occasions, maybe most of the time I don’t know, would say, ‘Well, yes, I think I think we can find funds to do that.’ The way he did that was simply in a large and arcane accounting system, you create a lot of accounts and you can just put funds away. . . There were a lot of little pots of money just tucked away for a rainy day.

“Lilly thought that the appropriate thing to do was to centralized these funds and make them an object for deliberate decision by the president and regents on how to spend it.

“Ironically, the Keller and Lilly central reserve was meant to bring these hidden funds into view, but the funds became known as a ‘secret slush fund.’”

Professor Foster also commented:

“When I first went to Morrill Hall, I did see directly some examples that I thought were absolutely shocking in behavior of individual regents in pursuing their own agendas, not necessarily political agendas either, personal agendas.”

Prof. Chambers asked, “Are there some for instances that you could share?” Prof. Foster replied,

“Well, seeing this waver in front of me about this going into the archives and being public, I can’t think of any at the moment.”

(Edward Foster, professor in the department of economics and the school of management, was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 28,1994.)

Wendell Anderson, who was a regent at the time, later said,

“At any rate, the regents didn’t know about it and they were a little upset about that. Maybe they should have known. Maybe they didn’t ask the right questions.”

(Wendell R. Anderson was interviewed by Ann M. Pflaum on June 1, 1999.)

I saw David Lebedoff at a community event while I was writing the book, and mentioned it. He eagerly shared that the central reserve fund was used for appropriate things, but the regents didn’t know anything about it.

The governor had suggested the University should spend the reserves, and legislators at the time seemed shocked that reserves existed. With the benefit of ten years hindsight, Representative Lyndon Carlson said in 1999,

“We have state reserves. In fact, I would view it the other way, that if a campus or a system didn’t have reserves, that probably would have put them at greater risk and would have raised more questions about management in at least my mind than having reserves.”

He explained that he served on the blue ribbon commission with then state auditor Arne Carlson (The Governor’s Blue Ribbon Commission on the Financial Management of the University of Minnesota) and others dealing with the question of reserves, and “There was broad consensus within that group, and there were others in the business community and so on, that the university should have a reserve and it should be minimally about five percent, which was very close to the amount that Ken Keller had in the reserve. So it was kind of the secrecy of it, the lack of knowledge about it that created the problem.”

(Lyndon Carlson, long-term representative in the Minnesota Legislature, was interviewed by Ann M. Pflaum on September 16, 1999.)

So, the reserves were appropriate, only the secrecy was the problem. The media had declared it a “secret slush fund.” How secret was it? When David Lilly became vice president, he explained, he told the regents they needed an audit committee. They formed one.

“[The central reserves were] an item on the balance sheet. The audit committee met with the auditors and the auditors went through every item on the balance sheet. This is the kind of world that suddenly dissolved then… everybody saying, ‘I didn’t know anything about that,’ There was no way you could say, ‘Well, you did, too.’ . . . the auditors had explained it to them; but we were employees, and they were the regents, . . . There was no question that if they hadn’t gotten Ken on that, they would have gotten him on something else.”

(David Lilly was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 11, 1994.)

Top left: The Minnesota Daily, October 12, 1989; top right: Minnesota Alumni Association magazine, September/October 1989; Bottom: Minneapolis Star Tribune, September 20, 1989.

Footnotes to the book

The following paragraphs were in footnotes in the original manuscript for Eastcliff: History of a Home. (When the publisher determined that the book was too long both for economical printing and reader interest, most of the footnotes were cut.)

Commitment to Focus and Kenneth Keller’s election as president

In the early 1980s, shortly after Ken Keller became provost and vice president for academic affairs, a recession caused Minnesota state revenues to drop and the State to be operating in the red (which is against Minnesota law). The University was required to return twenty-six million dollars to the State. According to Fred Lukermann, then dean of liberal arts, “Some people don’t know how close the University came to disaster. Keller held the deans to the grindstone and forced them to make some hard decisions. Believing that an across-the-board cut could ruin some excellent programs, University administrators required selective cuts. Keller supervised the development of criteria to determine a program’s importance to the mission of the University.” (Fred Lukermann was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers, September 16, 1984.)

Kenneth Keller was appointed interim president at the August 9, 1984, Board of Regents meeting, but not without much discussion, showing the split that had already formed in the Board. According to the regents’ minutes, after a motion to delay any appointment until September, “extensive discussion ensued,” and the motion failed. A motion was made that the interim not be a candidate for the permanent position, and remain in the position until the new president was selected. After a “lengthy discussion,” the second part of the motion was dropped, and a date of November 1, 1984, was added. This motion passed. Regents nominated seven people. Vice President Keller (only) was asked if he would abide by the proviso that he not be a candidate, he agreed. The other five nominees who were present asked for their names to be withdrawn. Kenneth Keller was elected as interim president on an eleven-to-one vote.

Ken Keller was interviewed in 1997, and explained the Catch-22 the regents forced on him:

“Minnesota meant and means a lot to me and I was not looking for an administrative role at a place that I didn’t have a connection to.” He had been pursued by other institutions. He continued regarding the University, “I’d spent my whole academic career here so that was a place I cared about. I had to think about this. At the same time, I’d been academic vice-president for five years during which time you make a lot of enemies. That’s fair enough. I said, ‘If I turn down the acting presidency, I’m essentially announcing to the world that I’m a candidate for president and I’m the only publicly announced candidate for president of the university.’ I said, ‘That is bound to lead everybody to think of all the reasons why Keller ought not to be president.’ Not only that, but when they choose somebody else, I am now somebody who has just the position of president and who is going to want to keep you as academic vice president? That didn’t make any sense to me. This clearly is a kind of no-brainer when you come to think of it.”

(Kenneth H. Keller was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on December 1, 3, and 8, 1997, on the University of Minnesota campus.)

In Ken Keller’s first regents meeting as interim president he presented a report outlining his views on the directions which the University should take in the interim period. In early 1985, he elaborated on this plan. Ken recalled, “for seven years the issues had been clear but we had vacillated about taking a position on one side or another of them. We had talked about what our choices were and we’d sort of made clear where we had to go but we had not bitten the bullet and actually come down on those issues. In those next weeks, I literally wrote it. I wrote it out by hand, gave it to Jim Borgestad and to George Robb who were people who helped and did some of the smoothing. We discussed it. Remember, the administration is now pretty bare bones because there is no academic vice-president since I was occupying both offices. . . I think what happened is that Jim Borgestad looked through the verbiage and found in it somewhere ‘commitment to focus,’ and he said, ‘This is it.’ Up it went and it became the title. I said, ‘Jim, you know better than I about these things. That’s fine.’ So, that was the title.”

(Kenneth Keller was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on December 1, 3, and 8, 1997.)

The plan was to clearly define the University’s mission and focus on areas of strength, reducing the University’s scope and size. The newspapers reacted to the plan with enthusiasm. (As described in the book, Governor Perpich had challenged the University to become more focused, and he was pleased with the plan.)

It’s important to note here that Nils Hasselmo served along with Ken Keller in the Magrath administration, as well, as vice president for planning and administration, so he was also part of setting the direction of the University. As you know now and they didn’t then, Nils would have a large role in enacting those plans.

Ann Pflaum interviewed Regent David Lebedoff in 1999:

“I cannot begin to tell you what a stirring response that document [Ken’s Commitment to Focus] caused. We got hundreds of letters and phone calls. So many wise and good people, respected people in their own communities and throughout the state, wrote to say, ‘This is it! This is what hasn’t been done and what needs to be done. Go for this!’ There was a huge amount of sentiment for Commitment to Focus, and it became well known around the country.”

The most controversial aspect of the Commitment to Focus plan was never actually part of the plan. The Campbell Committee was tasked with finding a way to balance the budget while anticipating decreasing state support. They recommended eliminating the schools of dentistry and veterinary medicine. President Keller respected the committee and appreciated their work, but strongly disagreed with their suggestion. When administrators received news of the report, David Lilly recalled, “That was the end of the world. We were all on a retreat, at that point, up on the Mississippi and somebody called in with what the Campbell Committee had recommended. Ken Keller said, ‘You’ve just sunk me!’ And it was true that that created the raison d’etre for the people who were against him in the first place, on the Board of Regents, to begin to go after him.”

In the regents’ meeting on March 7, 1985, the regents approved a motion that “the Board of Regents endorses generally the direction for focus of the University’s mission outlined in ‘A Commitment to Focus,’” by an eleven-to-one vote.

Ken Keller was serving as interim president. About two weeks before the end of the presidential search, Regent Lebedoff called Ken and asked him to be a candidate. Ken replied, “We have this resolution. I can’t be a candidate.”

On March 13, in a special meeting of the Board, the regents met and debated whether or not to overturn their resolution to not allow the interim president to be a candidate for the permanent position. They voted 9 to 3 to allow Ken Keller to be a candidate. This was exceedingly awkward because 1) Ken was required to be in the meeting, but for some reason was not supposed to be seated; he stood at the side of the room, and 2) When it was announced that there were two finalists for the position, and one of them was the current interim, the other candidate withdrew. The vote was nine-to-three over whether to advance their only candidate. After that vote (an hour into the meeting), Ken Keller was offered a seat and was then interviewed for two hours. After the interview, the Board voted eleven-to-one to elect him president.

The Eastcliff remodel

As Ken recalled it later,

“In Magrath’s Administration, Diane or Peter had set up a committee of people to look at what needed to be done at Eastcliff. There were big problems there, primarily having to do with how you entertained in the place but also having to do with the fact that there were rotting floors and a number of other things. . . At Peter’s suggestion to me, he said, ‘Get that taken care of before you ever move in. You can’t move in and do that.’ That made a lot of sense to me; so, in the negotiation with the group that was deciding this (I guess it was Lauris Krenik, and Lebedoff, and McGuiggan, and some others) we clearly agreed that there was a need to renovate Eastcliff and that I ought to hold off moving in until the fall and they ought to get that job done.”

(Kenneth H. Keller was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on December 1, 3, and 8, 1997.)

The spec book for the Eastcliff remodel construction is in the University’s engineering records office. In the first section of the scope of the project, there is a handwritten addition “Asbestos removal/encapsulation.” The change order section of the book makes up about forty percent of the three-inch binder. As I considered studying the book, I saw that there were more binders on the project, about twelve more inches of paper. I know how the story ends, so I didn’t read those many, many papers.

More landscaping work was envisioned, but not completed, including rerouting the driveway and making the entrance handicapped accessible (work done in the 1990s), and resurfacing the terrace around the pool (work done in 2011).

This full remodel was never finished. The glass fireplace doors were never installed, for example. In 2019 electricians replaced more original cloth-covered wiring.

David Lilly

The obituary of David Lilly (1918–2014) stated, “He served in the South Pacific for three and a half years, working on the resupply of 150–200 ships in the US fleet while stationed in Australia, a management-by-fire experience that was to influence the rest of his career.” That career began at the Toro Company in 1945, where he stayed until he retired as president in 1978. The he was appointed to the Federal Reserve Board in Washington. After his second retirement, he became dean of the University of Minnesota College of Business Administration, which he renamed the School of Management. (It is now the Carlson School.) After that retirement, he was appointed vice president for finance and operations at the University. He retired from that position in 1989.

Regarding his role at the University, David Lilly said, in 1994, “I felt and I told the people when I went in there that there was only one reason that we were there, and that was to service the students and the faculty, that we didn’t have any other justification. . . . We shouldn’t be hiding the assets and playing games with them. That’s when I went through all of the accounts and there were little pockets. . . Little reserves . . . You’ve got a great big cash machine here, and you’ve got a lot of cash that’s coming in, and before you use that cash, you can invest it. There’s a lot of temporary income that’s coming in from that cash.”

He continued, “The whole budgetary system, fund accounting here, is a wonderful device to confuse everybody. I wasn’t [able to monitor all of these scattered funds] but I was able to gather together a lot of funds that were under my supervision and put them all together into the president’s contingency fund. Then, we invested it well, too. There’s a genius over there by the name Roger Peschke, who was the treasurer, investment officer actually; and he managed all of the cash and he did a marvelous job investing it. During my period, we doubled the net worth of the university, if you will.”

(David Lilly was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on October 11, 1994.)

Ken Keller said, in 1997, “David worked assiduously with my support—we worked together—to bring all of those little pots of money that existed all over the university into a central reserve with the idea that each year, we would make some central decisions looking at the list of priorities for special projects for the institution and find out which of them we could fund out of these reserves, rather than allowing all of them to be spent and held by whatever process or serendipity might lead to them being held.”

(Kenneth Keller was interviewed by Clarke A. Chambers on December 1, 3, and 8, 1997.)

In the aftermath of President Keller’s resignation, Governor Perpich withdrew support for Commitment to Focus. After Nils Hasselmo was elected president, he and Pat had newspaper reporters and the public visit the house, and they regularly reported that the renovations were appropriate and not lavish, nonetheless the house and the University received increased scrutiny.

The catering kitchen was regularly described as costing $600,000, with some newspaper articles suggesting it should have cost less than $200,000.

The catering kitchen was actually built

and equipped at a cost of $187,000.

When newspapers were advised of the discrepancy between the circulating rumors and the facts, they were said to reply, “If you think the number means anything, you don’t understand what the issue is about.”

Please note: The above text was edited from Eastcliff: History of a Home due to lack of space. It is intended as a supplement to the book.